First-order continuous-time implementation

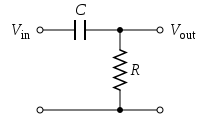

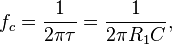

The simple first-order electronic high-pass filter shown in Figure 1 is implemented by placing an input voltage across the series combination of a capacitor and a resistor and using the voltage across the resistor as an output. The product of the resistance and capacitance (R×C) is the time constant (τ); it is inversely proportional to the cutoff frequency fc, at which the output power is half the input power. That is,

where fc is in hertz, τ is in seconds, R is in ohms, and C is in farads.

Figure 2 shows an active electronic implementation of a first-order high-pass filter using an operational amplifier. In this case, the filter has a passband gain of -R2/R1 and has a corner frequency of

Because this filter is active, it may have non-unity passband gain. That is, high-frequency signals are inverted and amplified by R2/R1.

Discrete-time realization

Discrete-time high-pass filters can also be designed. Discrete-time filter design is beyond the scope of this article; however, a simple example comes from the conversion of the continuous-time high-pass filter above to a discrete-time realization. That is, the continuous-time behavior can be discretized.

From the circuit in Figure 1 above, according to Kirchoff's Laws and the definition of capacitance:

where Qc(t) is the charge stored in the capacitor at time t. Substituting Equation (Q) into Equation (I) and then Equation (I) into Equation (V) gives:

This equation can be discretized. For simplicity, assume that samples of the input and output are taken at evenly-spaced points in time separated by ΔT time. Let the samples of Vin be represented by the sequence  , and let Vout be represented by the sequence

, and let Vout be represented by the sequence  which correspond to the same points in time. Making these substitutions:

which correspond to the same points in time. Making these substitutions:

And rearranging terms gives the recurrence relation

That is, this discrete-time implementation of a simple continuous-time RC high-pass filter is

By definition,  . The expression for parameter α yields the equivalent time constant RC in terms of the sampling period ΔT and α:

. The expression for parameter α yields the equivalent time constant RC in terms of the sampling period ΔT and α:

If α = 0.5, then the RC time constant equal to the sampling period. If  , then RC is significantly smaller than the sampling interval, and

, then RC is significantly smaller than the sampling interval, and  .

.

Algorithmic implementation

The filter recurrence relation provides a way to determine the output samples in terms of the input samples and the preceding output. The following pseudocode algorithm will simulate the effect of a high-pass filter on a series of digital samples:

// Return RC high-pass filter output samples, given input samples,

// time interval dt, and time constant RC

function highpass(real[0..n] x, real dt, real RC)

var real[0..n] y

var real α := RC / (RC + dt)

y[0] := x[0]

for i from 1 to n

y[i] := α * y[i-1] + α * (x[i] - x[i-1])

return y

The loop which calculates each of the n outputs can be refactored into the equivalent:

for i from 1 to n

y[i] := α * (y[i-1] + x[i] - x[i-1])

However, the earlier form shows how the parameter α changes the impact of the prior output y[i-1] and current change in input (x[i] - x[i-1]). In particular,

- A large α implies that the output will decay very slowly but will also be strongly influenced by even small changes in input. By the relationship between parameter α and time constant RC above, a large α corresponds to a large RC and therefore a low corner frequency of the filter. Hence, this case corresponds to a high-pass filter with a very narrow stop band. Because it is excited by small changes and tends to hold its prior output values for a long time, it can pass relatively low frequencies. However, a constant input (i.e., an input with (x[i] - x[i-1])=0) will always decay to zero, as would be expected with a high-pass filter with a large RC.

- A small α implies that the output will decay quickly and will require large changes in the input (i.e., (x[i] - x[i-1]) is large) to cause the output to change much. By the relationship between parameter α and time constant RC above, a small α corresponds to a small RC and therefore a high corner frequency of the filter. Hence, this case corresponds to a high-pass filter with a very wide stop band. Because it requires large (i.e., fast) changes and tends to quickly forget its prior output values, it can only pass relatively high frequencies, as would be expected with a high-pass filter with a small RC.

Applications

Audio

High-pass filters have many applications. They are used as part of an audio crossover to direct high frequencies to a tweeter while attenuating bass signals which could interfere with, or damage, the speaker. When such a filter is built into a loudspeaker cabinet it is normally a passive filter that also includes a low-pass filter for the woofer and so often employs both a capacitor and inductor (although very simple high-pass filters for tweeters can consist of a series capacitor and nothing else). An alternative, which provides good quality sound without inductors (which are prone to parasitic coupling, are expensive, and may have significant internal resistance) is to employ bi-amplification with active RC filters or active digital filters with separate power amplifiers for each loudspeaker. Such low-current and low-voltage line level crossovers are called active crossovers.[1]

Rumble filters are high-pass filters applied to the removal of unwanted sounds near to the lower end of the audible range or below. For example, noises (e.g., footsteps, or motor noises from record players and tape decks) may be removed because they are undesired or may overload the RIAA equalization circuit of the preamp.[1]

High-pass filters are also used for AC coupling at the inputs of many audio amplifiers, for preventing the amplification of DC currents which may harm the amplifier, rob the amplifier of headroom, and generate waste heat at the loudspeakers voice coil. One amplifier, the professional audio model DC300 made by Crown International beginning in the 1960s, did not have high-pass filtering at all, and could be used to amplify the DC signal of a common 9-volt battery at the input to supply 18 volts DC in an emergency for mixing console power.[2] However, that model's basic design has been superseded by newer designs such as the Crown Macro-Tech series developed in the late 1980s which included 10 Hz high-pass filtering on the inputs and switchable 35 Hz high-pass filtering on the outputs.[3] Another example is the QSC Audio PLX amplifier series which includes an internal 5 Hz high-pass filter which is applied to the inputs whenever the optional 50 and 30 Hz high-pass filters are turned off.[4]

Mixing consoles often include high-pass filtering at each channel strip. Some models have fixed-slope, fixed-frequency high-pass filters at 80 or 100 Hz that can be engaged; other models have 'sweepable HPF'—a high-pass filter of fixed slope that can be set within a specified frequency range, such as from 20 to 400 Hz on the Midas Heritage 3000, or 20 to 20,000 Hz on the Yamaha M7CL digital mixing console. Veteran systems engineer and live sound mixer Bruce Main recommends that high-pass filters be engaged for most mixer input sources, except for those such as kick drum, bass guitar and piano, sources which will have useful low frequency sounds. Main writes that DI unit inputs (as opposed to microphone inputs) do not need high-pass filtering as they are not subject to modulation by low-frequency stage wash—low frequency sounds coming from the subwoofers or the public address system and wrapping around to the stage. Main indicates that high-pass filters are commonly used for directional microphones which have a proximity effect—a low-frequency boost for very close sources. This low frequency boost commonly causes problems up to 200 or 300 Hz, but Main notes that he has seen microphones that benefit from a 500 Hz HPF setting on the console.[5]

Image

High-pass and low-pass filters are also used in digital image processing to perform transformations in the spatial frequency domain.[citation needed] The so-called Unsharp Mask used in most of the image editing software is a high pass filter.

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar